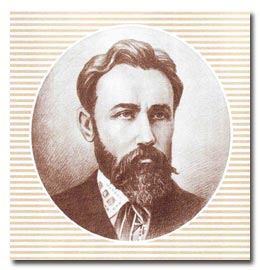

Borys Grinchenko, a famous Ukrainian writer, translator, publicist, literature researcher, linguist, ethnographer, and teacher, is well-known for compiling the first Dictionary of Ukrainian Language, writing textbooks for young students, being an editor of newspapers and magazines, and an active participant of the Ukrainian cultural movement. His mission in life was “to make a nation out of blocks”. Borys Grinchenko’s contemporaries remember him as a true servant who devoted his life to Ukraine. Mykola Lysenko, a Ukrainian composer, once said “He looked at Ukraine as a whole with his inspired eyes, observed it, saw its helpless state and decided to give his life to serve it, trying to satisfy its cultural needs all by himself”.

Borys Grinchenko was born on 9th December, 1863. As a child he fell in love with Ukrainian language, folklore, legends and traditions, started to assemble his own dictionary of Ukrainian language, not knowing yet that this material would later grow into a real dictionary. When Borys reached his teenage years, he began writing stories and poems, as well as his own journal. At the age of 15 he was arrested for distributing prohibited literature (books in Ukrainian were banned at that time). He bravely suffered through imprisonment and the consequences that followed (expulsion from university and prohibition to acquire any education till the end of his life; moreover, he was to be under police surveillance for the rest of his life). But Borys dreamed of becoming a teacher, so he studied hard and passed the teacher exam, and then got an approval to teach in a distant village (“by miracle”, as he recalled later). This profession, in Grinchenko’s opinion, would allow him to foster the cultural growth of peasants and change Ukraine for the better. He followed the German philosopher Leibnitz, who once said, “The one who holds enlightenment in his hands, can change the face of the Earth”. To reach even more people, Borys wrote school textbooks in the Ukrainian language, grammar and literature, striving to build his teaching on history, traditions and folklore of Ukraine. He was highly respected by colleagues for his dedication to teaching, sharp mind and love for children. Grinchenko described his educational views in a number of articles he published over years.

There, in the village he also met his wife, Maria Gladylina, who was a teacher, either. Their marriage was blessed not only with love, but also with determination to serve the enlightenment of Ukrainian people.

After a few years of teaching, Grinchenko’s family settled down in Chernihiv, a small Ukrainian town not far from Kyiv. Grinchenko worked in the document handling department and later as the Town Council secretary. Occupying these titles he did a lot for teachers, trying to improve their living and working conditions, supported the opening of new libraries and schools. He also contributed to launching and development of museums. Grinchenko started his work as a folklorist, ethnographer and bibliographer, collecting and publishing the folklore of Chernihiv region. He continued writing prose and poetry himself, but spent very little time on it, thinking that he “was never a poet who could devote all of his life to a song”. He said “I have always had very short moments for poetry, when I was free from labour, which sometimes was pleasant and dear for me, and more often it was very boring and tedious work”. Grinchenko’s stories, alongside with the stories of his contemporaries, lied in the basis of Ukrainian children’s literature, depicting moral and ethical problems of peasant children. As a teacher, Borys realized the importance of fairy tales for a child’s education, so he wrote about 20 fairy tales that were later published as a book.

Grinchenko’s family founded a publishing house in Chernihiv that published inexpensive and popular literature for the people. Since they were short of money, Borys and Maria Grinchenko did all the preprint work by themselves, managed to publish 45 books, and the total number of copies reached 180,000. Some of the money came from charity and sponsors, and some of it was invested by the family, though they had very little left for their living.

In 1902 the family moved to Kyiv and Grinchenko devoted most of his time to the Dictionary of the Ukrainian Language. His titanic effors and love for his work resulted in its completion within two years. The four volume dictionary was published in 1907-1909. In Kyiv, Grinchenko also worked as an editor and director of a magazine and newspaper, and head of a cultural and educational organization, Prosvita. He continued to put together their family library where he collected a lot of volumes about Ukraine. In his will, Grinchenko asked to keep the library as a whole, register it a separate catalogue and place books on special bookshelves, and call it Maria and Borys Grinchenko Library. His wife did her best to carry out his will.

Anastasiia Grinchenko, Borys and Maria’s daughter, was inspired by her father’s example and became a writer and translator, too. Seeing how deeply her father cared about the Ukrainian nation, she entered the Ukrainian Revolutionary Party, was soon arrested and died shortly after giving birth to a son who died four months later, too. The loss of his daughter and grandson, his mother’s passing away, and Maria’s illness (which happened within two years) caused an outbreak of tuberculosis in Borys. Maria borrowed some money from her father and took her husband to Italy to treat his illness. The couple settled in a small town, Ospedaletti. Unfortunately, Grinchenko was too weak and not able to overcome the illness. On 6th May, 1910 he passed away. Italian media called him “a great person, who worked for his country all of his life, and gave it his only daughter.” Mykhaylo Kotsiubynskyi, a writer and his contemporary, wrote to Maria, “We, and all Ukraine, should comfort ourselves by the thought that he has been among us, that his great work, his great love for his nation will never die and through them he will live among grateful descendants for a very long time”.

Borys Grinchenko was a model servant leader. All his life and energy were devoted to serving others and helping them “grow as persons… become healthier, wiser, freer, more autonomous and more like themselves to become servant leaders” (Robert Greenleaf’s criteria for servant leadership). His teaching and administrative career helped many people have a better life and have more access to education and culture, and Grinchenko’s books and articles have helped a great number of children and adults in mastering the art of their native language, as well as the art of teaching. As a founder and leader of a cultural society in Kyiv, Grinchenko helped many poets, writers, artists, and historians find their voice and calling in life.

Borys Grinchenko’s contemporaries remembered him as a person truly devoted to serving his nation and helping other people see how they could serve their communities and their country. He inspired people to work hard for the well-being of their Motherland. Hard work was one of Grinchenko’s core values, and this allowed him to be great in so many things.

“I’ll do it” – beware this word,

“I’ve done it” – this is the language of the mighty.

KUBG Academic Board at Borys Grinchenko monument opening ceremony in August 2011.